Joe Read online

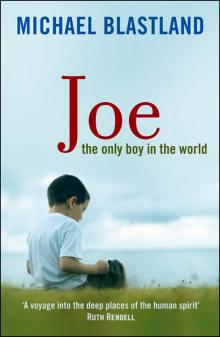

Joe

‘A remarkably readable and compelling book, offering much of value, at many levels. Michael Blastland, an erudite, incisive, thoughtful and articulate BBC producer, has provided us with an entertaining and educational account of life with Joe, his ten-year-old prototypical, severely autistic son. Read it. Enjoy it. Learn from it. It will haunt you.’ Bernard Rimland, PhD, director of the Autism Research Institute, founder of the Autism Society of America, technical consultant for Rain Man

‘A moving story … Blastland has performed a remarkable service in baring his family life for us.’ Simon Baron-Cohen, Guardian

‘Deeply personal and moving … Blastland’s beautifully written book offers us a glimpse of the torments endured by the growing number of children born with their cerebral pathways wrongly wired.’ Val Hennessy, Daily Mail

‘From this careful, serious book emerges a man with a quick wit and far-seeing eye for what makes life so peculiar … [Joe] stands out as a work of rare enlightenment’ Melissa Katsoulis, Sunday Telegraph

‘[Blastland’s] honesty is in keeping with a compelling, brave and highly readable book that never verges on the sentimental.’ Julie Wheelwright, Independent

‘This is one of the best books on autism ever written … In a vividly engaging style, Michael Blastland writes about his experiences not only from a personal perspective, but also a sound scientific one. Nobody has come closer to describing the awesome elemental force of autism, and the breath-taking innocence of the autistic child. If you want to know what classic autism is like, close-up and personal – and how autism can provide deep philosophical insights about your own consciousness – then read this book.’ Uta Frith, PhD, deputy director of the Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience at University College London and author of Autism: Explaining the Enigma

‘Blastland is likeably honest’ Julie Myerson, Daily Telegraph

‘If you read just one book about an autistic child this year, you would do well to make it this one.’ David Newnham, Times Educational Supplement

‘Joe is a book that deserves to be read. It will speak loudly not just to those interested in autism, but to anyone who is fascinated by the full range of what it means to be human.’ Tim Hall, Catholic Herald

‘No book has moved me more without sentimentality, or taught me more without didacticism, or entranced me more without obvious artifice. This is a sad, happy, harrowing, hopeful story, in which Michael Blastland – a father achieving understanding of his son’s autism – speaks with stunning objectivity, but never sacrifices passion.’ Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, Fellow of Queen Mary, University of London, and author of So You Think You’re Human and Pathfinders

MICHAEL BLASTLAND lives in a small village in Hertfordshire, often with his daughter Cait, less often and more noisily with his son Joe. A journalist all his professional life, he started on weekly newspapers before moving to the BBC where he makes programmes for Radio 4, including Analysis and More or Less.

Joe

The only boy in the world

MICHAEL BLASTLAND

This paperback edition published in 2007

First published in Great Britain in 2006 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

Exmouth Market

London EC1R 0JH

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright © Michael Blastland, 2006, 2007

S.O.S. Words & Music by Benny Andersson, Bjorn Ulvaeus & Stig Anderson

© Copyright 1975 Union Songs AB, Sweden.

Mamma Mia Words & Music by Benny Andersson, Bjorn Ulvaeus & Stig Anderson

© Copyright 1975 Union Songs AB, Sweden.

Take A Chance On Me Words & Music by Benny Andersson & Bjorn Ulvaeus

© Copyright 1977 Union Songs AB, Sweden.

Bocu Music Limited for Great Britain and the Republic of Ireland. Used by permission of Music Sales Limited. All Rights Reserved. International Copyright Secured.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Typeset in Goudy Old Style by MacGuru Ltd

[email protected]

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Bookmarque Ltd, Croydon, Surrey

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN-10 1 86197 944 4

ISBN-13 978 1 86197 944 5

For Joe and Cait

Contents

1 Fascination

2 Experience

3 Obsession

4 Language

5 Intention

6 Self-consciousness

7 Storytelling

8 Innocence

9 Seeing

10 Meaning

Postscript

Epilogue: Autumn 2006

Acknowledgements

Further Reading

1

Fascination

This book is about a boy called Joe. He’s ten and he’s my son. It’s a story of strange happenings and human riddles, it invites fantastical speculation and argues something brazen, preposterous even: that until you know Joe’s unusual life, you won’t fully understand your own.

Joe is a brown-haired, freckle-faced imp struck with an unusual variety of mental disability that leaves him at once vulnerable, charming and tyrannical. He digs his nails into your deepest sensibilities much as he digs them under your skin, wrenches you this way and that, and then, reaching his hand into yours or folding like a deckchair into a clatter of laughter, disarms you with innocence.

Ostensibly, he has little to say to the rest of us. He shares few of our pleasures, has many perplexing eccentricities and isn’t someone you’d instinctively turn to for enlightenment. Not quite the philosopher king, then. Joe is packed with strange urges and passions, missing many normal motivations and unable to make sense of the world in ways the rest of us take for granted – an odd one, to be sure. By and large such oddness is kept out of sight, tucked away in special schools or behind the shy doors of suburban semis where all too often families become isolated by love and the duty of care; that or the simple awkwardness of getting out and about with strangeness in tow.

Joe is now in a special school too, brought here into public view. I make no apology for throwing so much attention at him because with luck the result will be better understanding in two directions: ours of him, and ours of ourselves. Sadly, it might never run in the obvious third direction: quite probably he will never understand other people.

He started school in late August 2004. A small part of what follows is an account of the turbulent months surrounding that event. More riotously, the book relates some of the many moving and absurd episodes in his life that led us to the borders of madness, before which we never could have let him go; more recklessly, it uses my son’s history to investigate what makes the rest of us tick.

Joe was born with a perfect knot in his umbilical cord. Somehow, turning somersaults in the womb, he threaded himself through a loop in his own lifeline. There was a time when we thought this might explain his disability, but in all likelihood the knot had nothing to do with it, for there’s no damage to Joe’s brain of the kind that shows up in a scan as a result of oxygen starvation; no palsy. The only, and I have to say unconvincing, explanation was that his thoughts misfire owing to an entirely different, metabolic, cause – something to do with two of the amino acids that hel

p make up the chemical soup in his brain. Nowadays he lives with the label ‘autistic’: broad, ill-defined, ill-fitting and unexplained, a label that’s best put aside before getting to know him. But for me at least, and perhaps others who know his story, the loop in the cord became a metaphor: it framed a passage for Joe into an altogether alien existence that is magical, mysterious and infuriating in equal measure. When he tumbled into that oblique version of life, it was through the looking glass, through the doors of an enchanted wardrobe, while behind him the exit shut tight.

So unlike the birth of our first child, Cait, a dream of music and ease and elation, Joe’s arrival was frightening, the hospital disorganised, the breech birth undiagnosed, the pain-relief elusive until scandalously late. As Joe made his assisted way out, his pattering pulse ran into the sand and it was then that I noticed the room was stuffed with people. Joe’s foot was first to arrive: absurd, limp and bluish. Some cumbersome minutes later, but within seconds of his head and the swift snip of that cord, a man in a white coat scooped him to one side, gave him injections, worked silently, attentively, and cajoled the breath into him. So slow, so lazy was Joe’s embrace of life that we used to say it took a couple of months for him to agree that life was what he wanted.

In the years since Joe’s looking-glass moment, however it happened, his differences have always been mesmerising to me, but I’ve been, in a peculiar way, selfish with them. Part of the blame for my wanting to share them now lies with the historian Felipe Fernandez-Armesto, who forced me to declare my first ramshackle reflections, though I absolve him, naturally, of any responsibility for their content. Felipe and I bumped into each other one day outside my editor’s office at the BBC. Bumping into him is the one sure way of jolting Felipe into recognition, as his wife will testify.

‘Ah, Michael!’ he began, with typical ebullience. ‘How are you?’ Then, with the same tone and chirpiness: ‘And how’s your boy?’

I told him the latest. His smile barely faded; his prompt reply took me aback: ‘Fascinating! Fascinating!’

Fascinating? I’d been used to concern, appreciative understanding; used to sympathy, pity, remorse – not eager intellectual amusement. My much-cultivated sangfroid was altogether jumping in my veins at the thought. ‘Fascinating?’ As I realised instantly, but years late, Felipe was right, and in that unblinking moment I became dimly aware that it was possibly the most consoling thing I’d ever heard, and felt as though Joe sat high on my shoulders.

Fascinating. I’d long been fascinated by Joe, but I had reason. Now I was encouraged to think, as I had never quite before, that it wasn’t only a selfish fascination, that of course Joe is one of the most fascinating among us. Quirky, maddening, hilarious, adorable, hateful, sensitive, dangerous and exposed; he goes through his life’s repertoire on a fairground waltzer. Of course he deserves our attention, and when we give it, what things he tells us, what questions he asks.

As I tap these words onto a screen, Joe is upstairs sitting in bed during a holiday at home, chirping much later into the night than he ought. Today, an unexceptional day, he made a notable discovery: Daddy’s name can be spoken without strenuous effort a steady ten times a minute or more for what feels like a good hour and the effect is to send Daddy progressively bananas. That is, Joe would have learnt as much from this behaviour, if he learnt. The fact is that in general he doesn’t learn, or at least does so inch by painful inch, but the reason he doesn’t has a surprising way of showing us how we do – the different ways he has of seeing the world encourage us to reexamine our own.

The events in his life are sometimes mortifying, sometimes comical, poignant or weird, but above all for me now, they are fascinating. Fascination is one of the great consolations of this life of his, otherwise so frustrating, and I prefer that kind of consolation to pity; but thinking about Joe’s uniqueness pays doubly, with a deeper understanding of all our humanity than I could ever achieve by dwelling on my own.

What makes him fascinating? In part, seeing what we have in comparison to what he lacks. He makes much that we take for granted appear suddenly luminous, and we see equally starkly where we would be without it. As one eminent researcher put it, Joe’s condition teaches us ‘nothing less than the people-ness of people’.

Has he, then, become no more than an edifying puzzle? Not, I think, when his arms wrap around my neck with enough vice-like eagerness to mince vertebrae, when his voice chimes meaninglessly in selfless happiness with the pure clarity of bird-song, or when confusion and frustration muddy his handsome face, and I’m reminded that there can be no greater puzzle than the way we appear to him. At all times, as well as offering the rest of us fascination, he has a habit of continuing on his own sweet way without regard for what anyone thinks, a habit of continuing to be himself, oblivious to whether he’s fascinating or not.

I call him the only boy in the world because this is quite likely how it seems to him, living as he does without many of the commonplace nuts and bolts of ordinary human perception and understanding, in the absence of which he can never know even the elementary facts that he has kin and kind. That is, I think that is how it seems to him, because much is speculation, even among the experts, and Joe is in no position to put us right. And it has to be said that what I write may be true only of Joe and entirely at odds with the perceptions and experience of others on the autistic spectrum.

But the evidence, even if unique, is often compelling. The stories in these pages came about because Joe doesn’t do what most of us do, and do often without thinking, except when we’re nudged into reflection by seeing what goes wrong in those who aren’t so instinctively astute. While we manoeuvre through the fantastic complexity of ordinary living, managing to navigate human society with all its rules, rituals and expectations, Joe careers by in a circus clown’s exploding banger. If you observe his scrapes and confusions, you can’t help wondering how easy it is to go wrong and about the remarkable talents that mostly preserve the rest of us from disaster. What are these talents? How do we do it? Joe, by a kind of reverse engineering, helps to show us.

What we see when peering into his mental machinery is a child possibly lacking almost all the philosopher’s traditional definitions of what it is to be human. There is a list which varies a little but usually includes a high degree of self-awareness, sophisticated culture, rich use of technology or tool-making, a sense of our own history, structured language, an advanced ability to reason, complex moralities, the ability to think in abstraction or metaphor, and so on. I know the academic distinctions, I’ve read arguments from philosophy, neuroscience and elsewhere about what makes our species unique, or not. If I follow these distinctions, if I accept their logic, I’m forced to a rueful conclusion: Joe, my son, doesn’t qualify. If they are right about the attributes essential to being human, then I must face that chilling verdict. It is an outrageous question for a father to address, whether his child is one of us, but by suggesting that we can learn from him through the many ways he sets the rest of us in such sharp relief, I invite that question. How different can you be, how many fundamentals can you lack, and still be human? My head gives my heart some trouble on this, and though there can be no suspense about which side I favour in the end, I hope to reconcile head and heart in the following chapters. Part of what I hope Joe also shows us through these stories, once we see where the differences and similarities lie, is which are the ones that matter.

I remember when the decision about his immediate future weighed most heavily. ‘No point,’ one well-wisher said, ‘ruining your own life for someone whose life is already ruined.’ He was a kind man, a good man, who meant well and intended to console me, but the word burned. Ruined. I pictured a cartoon caricature of physical dereliction: a crumbling castle wearing Joe’s glummest face: roofless, remote, desolate in the tumbleweed. Was my son’s life a ruin – redundant and pointless? The thought revolts me, but say it is true? Say there is no hope?

All right, I reply, so ruins have no future and mig

ht be inhospitable, but more than any home comfort they incomparably fire the imagination, and so, even if for that reason alone, repay all the attention we can muster. Of course, I want better for Joe than that. This book has become my attempt to hoist him into view, not just as inspiration to the rest of us but as so much more besides. I hope it does justice to the confused, exuberant pinball that is Joe. I also hope you will find it a fine place for your imagination, that something here will leave you either fascinated by him or startled at yourself.

2

Experience

‘If you get lost,’ they said, ‘follow the signs to the zoo.’

‘Ha! Joe is going to live in the zoo,’ we laugh, as we pass signposts of elephants pointing the way, and silently share a more sombre thought: is he? It’s the summer of 2004 and Joe is due to be assessed for a place at a special residential school. He’s nine years old.

… And I think back to another day, in spring, at about eight o’clock, when Joe’s sister Cait was hustled out to the car for the morning rush and the front door closed on a still and silent house, all haste and muddle of the morning packed and bundled outside, Joe left behind.

Joe’s prospective new school, as it comes into view on the road past the Downs, is a row of aloof Victorian houses, beautifully set, not far from the river Avon at Clifton, Brunel’s suspension bridge atop the gorge as if to frame it, to please the eye more than shift traffic. We face an hour or two of meetings and a tour of the school to settle two questions: are they willing to have him and do we want him to go? The second is proving hardest. Other schools have places – all, like this one, far from home; all inadvertently feeding not calming our disquiet. Perhaps this will be different. I hope so, we’re running out of options.

… And I think again of that morning when Joe lay upstairs in bed, apparently asleep. I imagine his peaceful breathing and how, once awake, he’d stretch and lie singing an aimless melody, getting up only when he needed to. Seldom would he do anything without the whole house knowing.

Joe

Joe